Over the past decade, major scientific leaps have been made in regenerative medical research. Until recently, only tiny portions of functional human organs have been cloned or grown in-vitro.

In 2014, Researchers at Northwestern University announced the discovery of the gene zic-1 which seems to enable circulating stem cells to “regrow” the head of flatworm planarians after decapitation. There are several species across the animal kingdom that have shown the ability to regenerate organs and body parts, but the actual mechanism behind them such as stem cell activation were not fully understood.

Many developmental biologists now believe that most animals use “tissue organizers” to secrete proteins and cytokines that allow cell to cell communication that helps in the formation of the bodily organs.

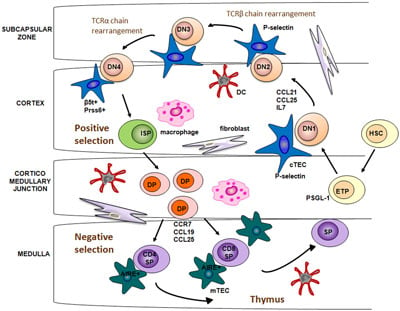

More recently, a researchers at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland managed to rejuvenate internal organs in mice by manipulating their DNA. This study is likely to have much broader implications for regenerative medicine. Researchers now believe that the thymus (near the heart) is responsible for producing T-cells to help fight off any infections humans have. The problem however is that for elderly patients, the thymus shrinks to just 10% of the size and capacity it has for adolescents.

This slow degenerative effect on our thymus has significant impacts for humans later in life. If the functionality of our immune system steadily decreases we become more and more vulnerable to serious infection and also significantly less responsive to any vaccines that get administered.

How to boost the Thymus

A team of specialists at MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh has finally been able to regenerate the thymus function in elderly mice by manipulating a gene called Foxn1. This gene was observed to “shut off” as the thymus aged, so the researchers tried several ways to boost it back to the functionality of young mice.

After several attempts, a compounded chemical was used successfully to increase the effectiveness and functionality of the Foxn1 gene in old mice. The gene therapy results clearly show that boosting Foxn1 levels in elderly mice can indeed give them the same effectiveness of the thymus as those of much younger animals.

The eventual goal is to help regenerate a human thymus using this exact method. Currently gene therapy for humans is experimental however researchers believe that their technique can be used safely in humans to increase the size and function of the Thymus to produce more T-cells. By targeting a single gene, the scientists believe they will be able to regenerate entire organs to more useful and potent states.

Degenerative effects of age on bodily function

Scientists have cautioned that they still are not certain why our thymus functions shrink with age. Some believe that this degeneration is due to our body allocating resources to more critical functions as we age. The key however is going to be to allow the regenerative capacity to return without causing in imbalance that could lead to the immune system going into overdrive causing itself to attack the body instead of healing it.

The need for healthy organs across the world is real. Each day, dozens of men and women across the world lose their lives waiting for organ transplants. The prospects of “bio-artificial organs” grown from the patients own cells is great however become much more difficult is the patients original organs and tissue are too damaged by cancer for example. The alternative targeted gene-therapy to regenerate failing organs such as heart or brain seems to be the best alternative to cloning human organs. Harnessing the bodies own repair mechanisms and manipulating them in a very controlled way through gene-therapy of single proteins is likely to be the single biggest accomplishment by humans in the 21st century.

Sources:

http://www.northwestern.edu/newscenter/stories/2014/07/tiny-worm-holds-healing-secrets.html

http://www.crm.ed.ac.uk/news/fully-functional-immune-organ-grown-mice-lab-created-cells

http://stemcellthailand.org/therapies/liver-disease-cirrhosis-hepatocyte/

Image source: Matthew Nakagawa, University of Edinburgh